I couldn’t make it to LA for this year’s Loop summit, but fellow musician and now also hardware builder Nicole Equerme graciously agreed to report back for us. While there were some live streams and interactive challenges for those of us who stayed behind, it’s great getting a perspective of someone who attended. It instantly had me transported back to the previous Loop summits I was part of. So if you haven’t been, this long, but entertaining article by Nicole should give you a very good idea of the experience.

Friday, November 9th

“You can’t do it all.” Sage advice from Dennis DeSantis, the brilliant author of Making Music: 74 Creative Strategies for Electronic Music Producers and official Welcomer of the Loop conference at the famous Montalban Theatre in Los Angeles, California.

He is right; on my official Loop app, I keep finding topics that pique my interest but overlap with other events I want to attend. I keep his advice in mind and try to plan for flexibility.

Sound and Vision: Composing for Films is the first event I attend. Drum & Lace and Jimmy LaValle speak with moderator David Reid about what it’s like to compose music for film: the intricacies of sampling, forging and keeping relationships with directors and writers, how to use different source material to set moods, etc. Jimmy LaValle had sampled his son crying— an innate human expression of pain, longing, want. He pitch shifted this sample and added synthesis to create a distinctly dark, gritty synth sound. Layering these notes into chords, he sets the scene for the dark indie romance “Spring”.

Sophia of Drum & Lace uses synth sounds and layers a human voice to create an emotionally moving piece behind a climactic scene of the documentary “Love and Bananas,” a documentary about elephants’ conservation in Thailand.

Next, I head over to Guitar Pedals as Sound Design Tools. The workshop is held by Dustin Ragland in the world-renowned EastWest Studios in Hollywood. Dustin is an adjunct professor of Music Production at The Academy of Contemporary Music at The University of Central Oklahoma, certified Ableton trainer, and analog pedal enthusiast.

He is talking about improvising, as a drummer, with a chain of analog effects pedals. He has just set up a percussive delay and tweaks the delay time, which causes a percussive eighth note repeat to kick in “I interpret that, in the moment, just by not thinking too much about what I’m trying to do to improvise with these pedals.”

Good advice. Thinking on the fly is not analyzing on the fly. When improvising, we must use the skills we have already honed, to musically react to the things around us.

“This is a whole world of composition working with electro-acoustics. Usually it’s like ‘oh yeah! A Stockhausen score! It looks like boxes and notation and staff’… but what I want to think about is how this acoustic sound in the space also combines with the sound that is coming out of the pedal(s). Not only is it the sound that’s been processed, but also the sound that is coming out and filling the space. If you’re in a space where you can not only use a reverb pedal but also think about the actual acoustic space that you’re in to be able to have that be a part of your sound as well…”

Space as part of “your” musical timbre: this is something so situational, it is impossible to notate in a score or really concretely explain. We rely on our previous experiences to help guide us to achieve a sound we want in any given space at any given time. Where the line is drawn between “noise and music” is a fine one (and some may even argue— a line that does not exist). To consider atmosphere/venue as part of “your” sound is drawing an even finer line between the “space/noise/music” relationship(s). I continue to think about this during the workshop…

“Thinking about the technical aspect of things… the simplest thing is to patch a guitar into a few pedals and put that into an amp. This is a nice little closed system where all of the levels and impedances work with one another. You know what you’re expecting and you get what you’re expecting. But the minute we start taking microphones, putting that into a microphone preamp, and then sending that at a line level output… that’s going to be a lot hotter than what the pedals are expecting, there’s three different things that need to happen to help that to come down. If you have just a simple mixer in your set up, you can use that to attenuate the levels, but the impedance needs to be matched in this. Impedance is just a resistance to flow signal, similar to resistance, but it is also very frequency dependent. So impedance that occurs inside of a guitar chain can often pull a lot of the high frequencies out of the signal passing through the chain. The same thing that’s going to happen if we send the wrong kind of impedance to these pedals; we’re going to get different kinds of frequency response depending upon the levels that we’re at and/or depending on how hot that signal is. So of course there are boxes that are intended to do this… usually re-amp boxes.”

He asks how many people in the workshop have heard about re-amp boxes. Only a few raise their hand. He clarifies a re-amp box’s purpose, answers a few questions with regard to situational uses of re-amp boxes, and then jumps into the practical part of the workshop— the pedals sitting on the tables in front of everyone. They are all connected to a mixer in the front of the room and he encourages the two groups to start experimenting with each table-full of pedals. Everyone here interacts freely and reacts to effects created by other folks at the table.

Saturday, November 10th

I attend Best Laid Plans a panel made up of Photay, Patrice Rushen, Laura Escude hosted by Dennis DeSantis about when things “go wrong.” This is a subject I am intensely interested in considering failure and I seem like best friends (for better or for worse). Whenever I mentioned the subject “failure” or “failing,” it seems like people always rush to reassure me about how great whatever it is I’m doing is… I find this puzzling considering failure is necessary to improve. The word “failure” has a negative connotation, but because I am constantly failing (in order to get better), I actually have come to love failure to a certain degree. I’m interested in hearing how other professionals feel in various stages and situations of failure…

Patrice Rushen shares a story about being a Music Director at an international awards show when Prince and Beyonce were supposed to be two of the main musical acts in the line up. After intense rehearsals to ensure everyone was on the same page about every nuance of the performance (musicians, camera men, and lighting included), at the last minute, a set of creative directors wanted Prince to perform “just acoustically.” It was so late in the day, there wouldn’t be another chance to rehearse before the live TV event. Patrice advised him to air on the side of caution and stick to what everyone had been rehearsing and to politely decline to change the show at such short notice. Everything went off without a hitch.

A near miss!

Photay shared his story of being sick with a fever so bad, that he had to sit in the airport infirmary with an IV and missed his initial flight for a show in South America. When he finally did make it there, he played an incredible show, fed both in passion and energy by the audience, finished his show, and promptly crashed for a solid day or two in his hotel before regaining the energy to continue on.

Sometimes the energy from an audience/crowd can make all the difference— both in how well we perceive we played, and also how well we actually play.

Dennis follows up with “If you had to choose between a massive catastrophe at a a low-stakes gig or a small one at a high-stakes gig what would you chose?( (Or is that too situational?)”

Laura answers, “I think a massive catastrophe at a low stakes gig…”

“So the stakes are what matter more for you…?” Dennis clarifies.

“Yeah,” she continues, “at a huge gig, even the tiniest thing is amplified. It’s just… you notice— people notice. And especially when you are on a tour with 20,000 that would notice a glaring mistake… I would rather something small happen… and most of the time in an arena, or with a crowd that size, people don’t notice the smaller mistakes… I don’t know… that’s just me. I’d much rather something small happen at a high stakes gig.”

Patrice jumps in, “I would tend to agree. There is so much that you do that is dependent upon your last success. Your next gig is dependent upon when somebody last saw you do something. So yeah, you always want the perception to be good. Since you learn stuff when you fail…I mean I happen to think that part of failure is a good thing because of what you learn from it, but you’d rather do that when are in a smaller situation, preparing for a major gig.”

Photay nods in agreement and responds “Small mishaps stick with me and can sometimes create a domino effect and I might screw up again if I’m thinking ‘that didn’t go as planned,’ but, with smaller gigs sometimes too, it feels more forgiving… for instance, I had a show that was the last show of a tour. Maybe I had practiced a little less for that show because of that and it was a smaller show… and on the first song, my kick drum attached to a MIDI pad just… didn’t sound. So there was an ambient pad that persisted and it was just… the most anti-climatic thing you could dream of. I just got on the mic and said ‘hey, I’m sorry it’s going to take a second for me to figure this out…’ and someone yelled out ‘it’s all good! We love you!’ And I just sighed in relief, but in a concert hall or something, you don’t really have that luxury.”

I stuck around after the panel discussion for a track deconstruction with Photay— I wanted to hear on a more musical level, what he had to say.

I was not disappointed. He deconstructed a track from an upcoming album that included him and a few of his friends going into a remote bunker, recording their voices sliding into improvisational harmonies with one another, and used that to spark the main theme of the track. He spoke about his fascination with convolution reverb, about the layering techniques he used to create some percussive sounds throughout the track, and even about his love of using “found sounds” in his work. He told a story about when he was younger, how his Mom bought the soundtrack of a train that ran for an hour or two— just a train running on the tracks with engine noises, bells, whistles, and various other sounds interspersed throughout. He said “my Mom would put it on in the car as we drove to school.” Everyone laughed at the absurdity of it.

Because there were back-to-back talks during the day, I continued hanging out at the Montalban Theatre for Start Here hosted by Andrew Huang. This was a sample challenge given to not only three of the folks on stage, but also given to the Ableton community on the Ableton website— the whole world participated.

Loop was, I found, always trying to spark conversation, interaction, and encourage the free exchange of ideas. This year, there were several online interactive activities (like the sample challenge in which a composer submitted a short clip for others to create music from). There were also live streams of a few major panel discussions and talks. This sort of free-exchange prompted me to head back over to East West Studios, which is where I found a lot of the smaller groups gravitating.

I was able to attend Intermediate Mastering with Daddy Kev (aka Kevin Marques Moo) in Control Room 5. The mastering engineer and owner of Alpha Pup Records talked about the importance of facilitating artistic vision via mastering, keeping and maintaining relationships as a mastering engineer, and “explaining what you think is sonically correct and then ultimately going with whatever they want to do.” We did dive into some technicalities, like when we spoke about the Fletcher-Munson Curve, which illustrates as the actual loudness changes, the perceived loudness our brains hear will change at a different rate, depending on the frequency.

Mostly though, we spoke about technicalities with regard to the client, which I thought was a really helpful lens though which to address these sort of things. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter which compressor you use or at what ratios you set them, so long as you achieve the desired result that your client wants to hear.

I snuck out of the mastering talk a few minutes early to attend the UX Design Meetup. I hadn’t yet gone to a meetup, and even though I am not a UX Designer (and, admittedly, had to look up what UX Design even was— it is the study and implementation of designing things to be as intuitive and user-friendly as possible), I thought it would be a fun space to meet people. I am in the process of designing a few hardware items myself, so I thought the meetup could be a potentially helpful one as well. Aside from my own personal design endeavors, who doesn’t want to help create the most intuitive world possible?

This was probably one of the best things I did at Loop. Smaller groups and conversations are really where I feel most at home, and these folks were particularly interesting— their view of the world was both logical and analytical, but in a creative “how can we do better” sort of way. While there, I met folks who worked in a variety of fields from Novation to NASA.

This helped to fuel my approach to the last day of Loop— another small group conversation.

Sunday, November 11th

How To Talk About Music: A Practical Guide was a small workshop held at East West Studios. Admittedly, I wanted to attend another session, but it was full, so I was shuffled over here. This small group, hosted by Craig Shuftan, spoke about language, conversation, how to dialogue and converse with other people, and in turn (taking these principles into account) how to talk about music with people. I was an English major who spent (and currently spends) a lot of time thinking about the art of conversation and dialogue, and by extension, communication in general, so this workshop was right up my alley.

We spoke about the reasons we communicate, the ebb and flow (give and take) of conversation, and even some of the politenesses of different cultures in conversation. Overall, an exceptionally thought-provoking workshop. An event I’m glad I got “shuffled into.”

Right after this was a Mastering Q& A with Emily Lazar. Considering that I have not only listened to records she has mastered, but also read a few articles on her and her mastering career, I was truly excited to be present. Like Daddy Kev, she also spoke about the important relationship between the mastering engineer and the client, and how, as a mastering engineer, it is your job to guide and inform, but ultimately, the client decides how they want to execute their artistic vision. I admired her candor especially regarding subjects like gear. Her general attitude was: educate yourself. Know the rules in order to break them. Knowing the strengths and weaknesses of your gear is great, but at the end of the day, it isn’t about the specificities of the gear (what compressor you use, or what setting it is at), it’s about making your client happy. And you have to be willing to think outside of the box in order to make that happen. “That’s kind of the trick is being able to find these different combinations of things… and of course, it really does rely on the artist you’re working with, the material, and the people in the room, and the current in Berlin versus here, and the sounds of equipment… and the technical things that are involved: if the equipment is hot, or how long it’s been sitting on, if it’s cold, how long the cables are, all sorts of interesting, geeky things… all of these things matter.”

“But, ultimately, I love the fact that in your bedroom,” she gestures to a man who previously introduced himself as a bedroom producer, “you can make something that is like something I’ve never heard. I love the ability to be able to do that. I don’t think that you have to necessarily have all this stuff to achieve a great result. I do believe that the mastering side of things is a little trickier because in today’s world we’re dealing with a lot of different formats and there’s a lot fo media you have to distribute through [which are all very different masters]. Hopefully in the next few months, we’ll be able to get everybody under control and have some real data points to say ‘this is how we’re going to submit to this.’ Right now it’s a little Wild West-ish, so… one of the biggest complaints I’ve heard are from people making music in their bedroom, putting it on Spotify, and then saying ‘it sounded so amazing to me, and then I put it up there and now it sounds awful and quiet and I don’t understand…’ so… there’s a lot of things that a mastering engineer can help guide you and understand.”

She went on to talk about Spotify’s “Normalize” feature— a feature several people in the talk did not even know existed.

I had a question… something that had been on my mind and one I had posed in various instances, since yesterday morning: “Is there a particular instance or song or record, or some instance in your mind that you consider a ‘failure’…?”

“Oh my god, there are so many!” she responded.

“What is an epic one that you might be able to recall…” I prodded…

“So many…” she continued. Then she stopped and paused for a long while. “I think that is a really interesting question because I kind of think everything I do is a failure until the person’s like ‘I love it!’ Truthfully.”

I connected with her in that instant because, I feel somewhat of the same way also. She went on to say that if she “fails” at something, it is just encouragement to her to make it better next time. And that, is exactly why Emily Lazar is such a badass in her field.

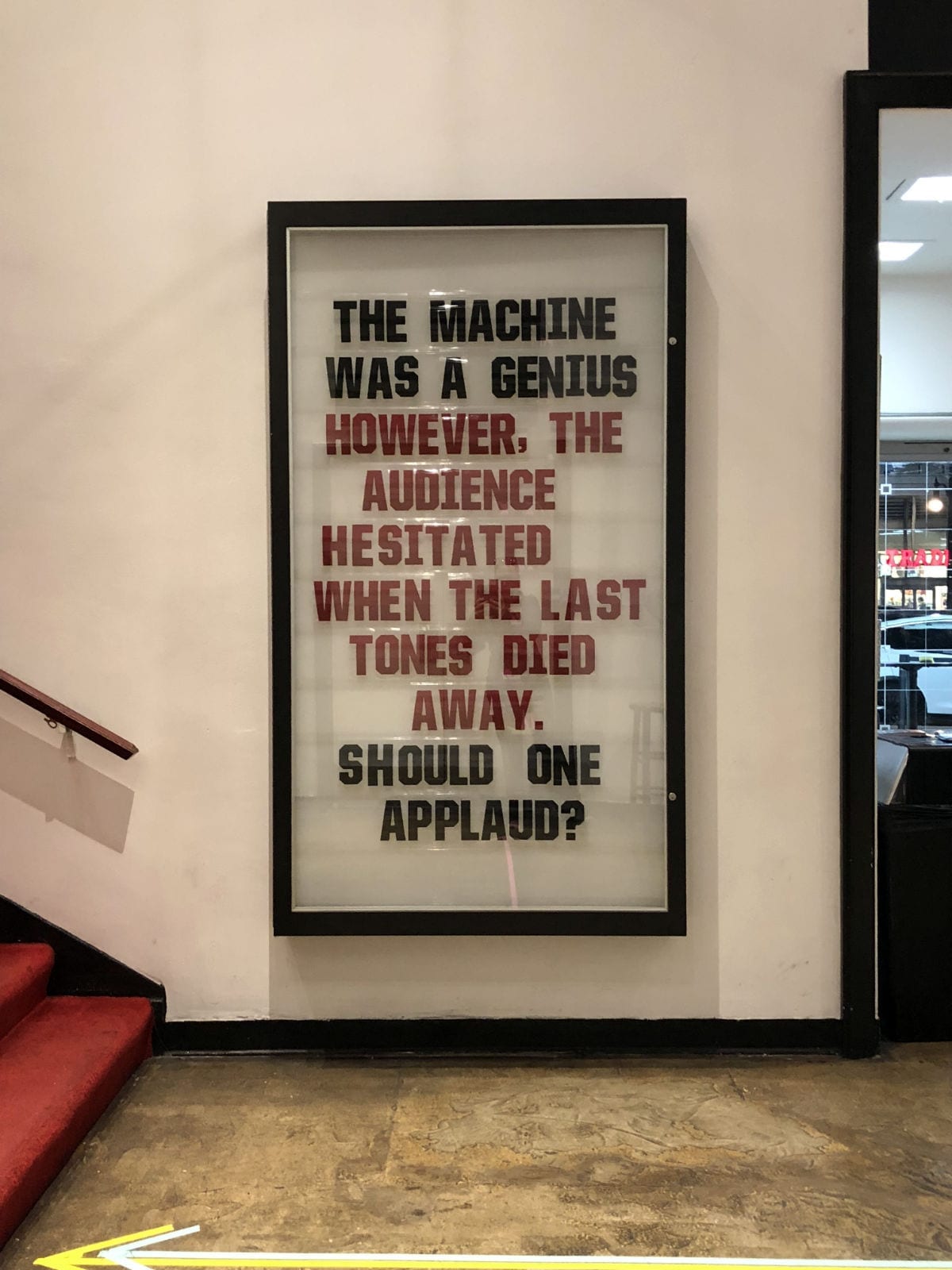

After the Q&A, I briefly attended Teaching Yourself To Make Music Software: Steve Duda in conversation, in which Duda dives into his thought processes for creating the VST plugin ‘Serum.’ The delving into his creation was admittedly a bit too technical for me to understand— STACK OVERFLOW. But, I did enjoy watching his time-lapsed video of the evolution of Serum.

The Closing Address from Dennis DeSantis followed by The Kid live performance by Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith were the last two items on my agenda, both of which left me with an ellipses of intrigue and wonder as to what will be featured next year at Loop 2019.